Basics of hardware hacking

This course shows the basics of hardware hacking using password auhenticaton code as an example.

Created by @maldr0id

Limiting the password attempts

Limiting our password checking routine to only three password guesses is a bit challenging, because the number of guesses has to persist across CPU reboots. EEPROM.write and EEPROM.read are methods which are used to manage persistent memory on Arduino. The first argument for both methods is a memory address – the place where we will be storing our counter.

bool checkPass(String buffer) {

byte tries = EEPROM.read(TRIES_ADDR);

if (tries == 0) {

return false;

}

bool result = true;

for (int i = 0; i < PASSWORD.length(); i++) {

if (buffer[i] != PASSWORD[i]) {

result = false;

}

}

if (result) {

EEPROM.write(TRIES_ADDR, 3);

} else {

EEPROM.write(TRIES_ADDR, tries - 1);

}

return result;

}

The method first checks if there are any password tries left. If there aren’t any it returns false. If there are some tries left it will perform regular password validation and then decrement the counter, if needed. Now we can rest easy that our password check routine is secure.

Well, not really.

The thing is that in the main code we have this:

bool correct = checkPass(pass);

if (correct) {

Serial.println("Password correct!");

This means that there is a single point of failure – if the execution of checkPass fails (for whatever reason) and erroneously produces true the board will be unlocked with a Password correct! message.

This is a point in the training where most of the participants have either a very confused look or think I’m joking. It’s fine if you had the same reaction, as the rest of this course deals with what can be safely described as “magic.”

If we can somehow inject a fault and make the checkPass method believe that the password is correct we can unlock the board. We do not even have to know the password in order to do that. ATMega328 CPU, like all electronics, has a minimum operating voltage. It’s unclear what happens if the voltage drops below that threshold for a very, very small amount of time.

In our imperfect mental image we can imagine that the CPU would like to draw some power to flip a bit, but we turn off the power supply for that very short moment and it’s not able to do that. However, we turned the power for such a small amount of time that it didn’t power down the CPU. It has entered an erroneous state. This is what we will try to attempt.

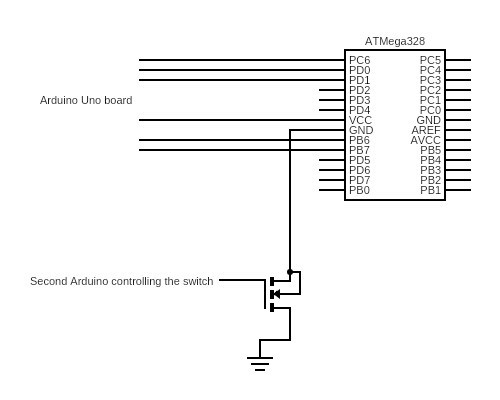

In order to drop a voltage for a very small amount of time we will use a transistor to act as an electronically operated switch. We will use a second Arduino board to control that transistor and very quickly turn the voltage off and on in hopes that are target Arduino won’t notice that.

The circuit looks like this:

The transistor is responsible for switching the power on and off. Most of the time the power will be on (otherwise the CPU won’t work) and the second Arduino board will turn it off for a very short time - few CPU cycles. Since we don’t know or care how long the glitch (i.e. the action of turining the power off and on) should be, we are going to try different values in this very simple Arduino code:

int waste = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < glitchOffset ; i++) { waste++; }

digitalWrite(glitchPin, LOW);

for (int i = 0; i < glitchLength ; i++) { waste++; }

digitalWrite(glitchPin, HIGH);

delay(100);

glitchLength *= 2;

if (glitchLength > 10000) {

glitchLength = 1;

glitchOffset *= 2;

}

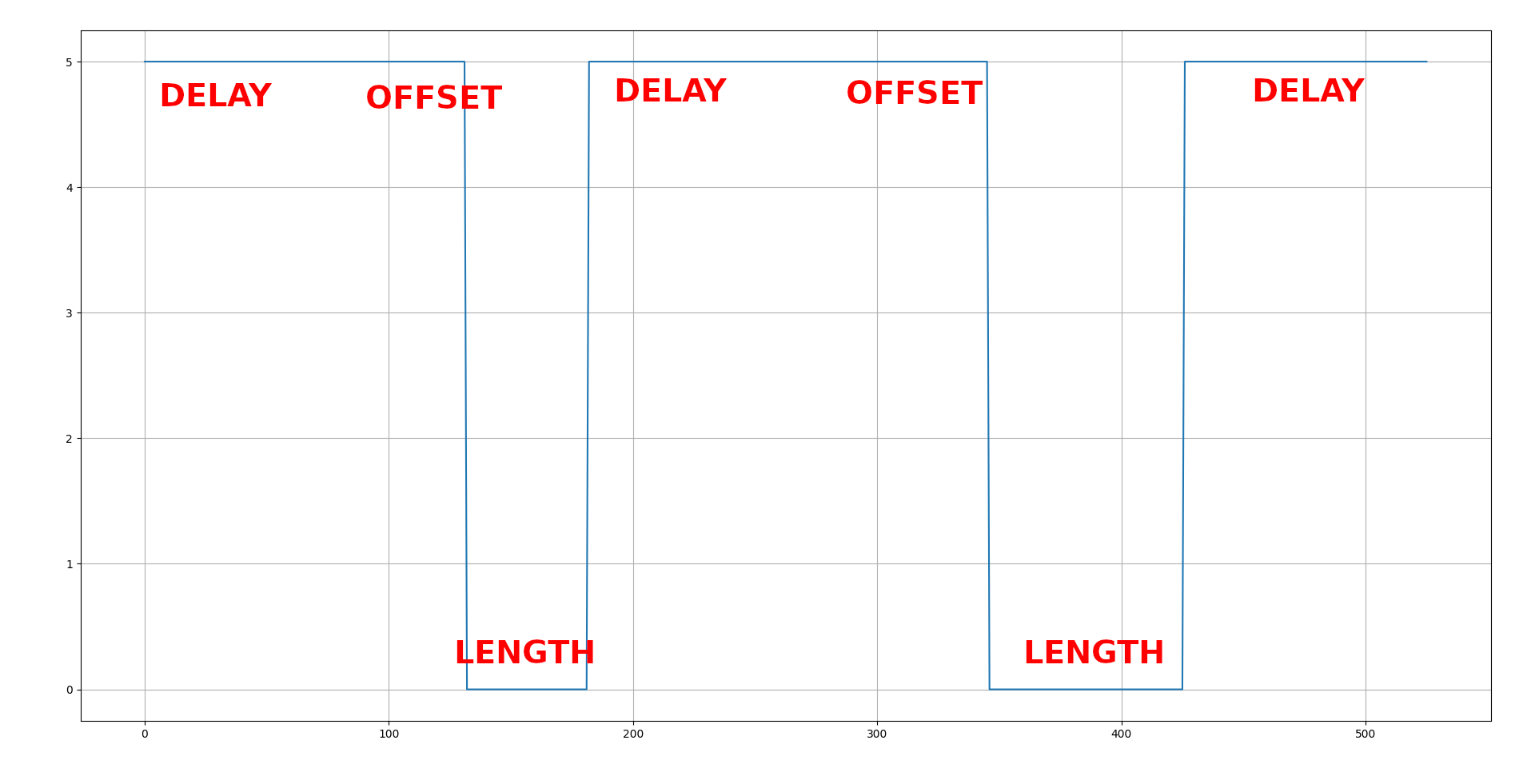

There are two parameters in this code: glitchOffset and glitchLength. The first one decides when to start glitching and the second one decides how long to glitch for. There’s also a delay of 100 ms in order to stabilise the current. Otherwise we could run into a situation where glitching happens so often that there’s not enough power to turn on the CPU. Take a look at the chart below.

Of course there’s no difference to voltage between the delay and the offset glitch, but the delay is constant and the offset changes length. You can also see that the glitch length get progressively bigger. Now that we have our circuit, we have the second Arduino controlling the transistor, we have the transistor that quickly turns the power off and on, we can start glitching. What does the glitching look like? Take a look at the serial output in the GIF below.

It’s important to note that we are not actually sending any data to the board. Any password guess at all. The CPU itself displays all the information because of the glitching. You can see at the end that we got the Password correct! message without providing any password. This happened even though the board was locked and didn’t allow any password guesses! Isn’t this magical?

It’s time for a summary and - if you still have questions left - a bit of a FAQ.